Hitting Refresh: The Landlord (1970)

Dir. Hal Ashby

Hal Ashby's early film career involved working as an editor for Norman Jewison, which garnered him an Academy Award for In the Heat of the Night and performing some game-changing split-screen work on The Thomas Crown Affair. Taking the advice of Jewison, Ashby stepped up to the role of director for the racial satire The Landlord and made a film debut that is alternately hilarious and moving while still managing to showcase some avant-garde editing as well as some of the more experimental work of master cinematographer, Gordon Willis. In other words, Ashby took his first at bat swinging for the fences.

Adapted for the screen by Bill Gunn, a central figure in 1970s black cinema who went on to write and direct the classic Ganja & Hess, The Landlord stars a baby-faced Beau Bridges as Elgar Winthrop Julius Enders, the son of a very wealthy and WASPy family, whose young rebelliousness leads him to purchase a tenement building in Park Slope, New York. Given the eager and willing pedigree of Ashby, Gunn and Willis, the movie isn't afraid to take some chance when it comes to its visual storytelling; but after a disarming introduction that takes the form of a faux documentary, and some jump-cut juxtaposing of 1970 Park Slope against Bridges' country club upbringing, the film settles in to a more straightforward narrative structure. While there are highly stylized flourishes throughout, at its heart, The Landlord is a simple story of growing-up and finding love and independence -- it's like the new-wave, east-coast version of The Graduate.

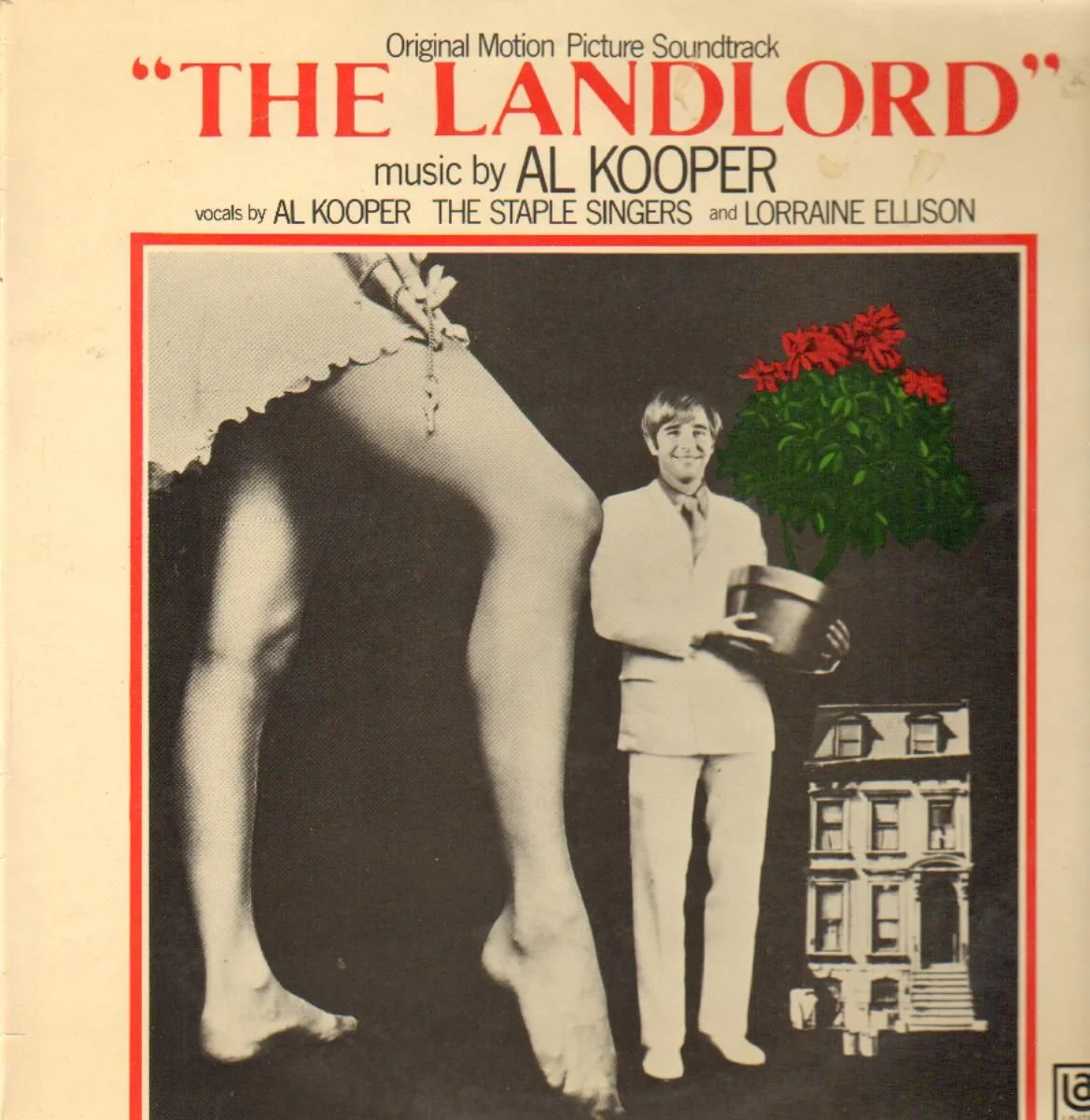

Soundtrack album cover for The Landlord

And though it may not have The Graduate's reputation, I think it's fair to say this particular slice of satire is a whole lot funnier. There's great joy to be had in watching Bridges have his idealistic notions of being a Park Slope landlord dashed as he meets his tenants one-by-one. His awkward introductions to the women of the apartment make for some particularly hilarious moments.

What makes these scenes, and the rest of the movie, rise above even some of the best fish-out-of-water stories is how genuine the characters are. Remarkably, especially for a counter-culture comedy, this film is free of stereotypes -- instead they're conflicted and contradictory and they all shine brightly because of it. I defy you not to fall in love with Francine, the tenant played by Diana Sands (whose own life story is quite tragic), root for Elgar and even feel sympathy towards Elgar's racist mother (played by Lee Grant in a well deserved Oscar nominated performance). Every character here grows, evolves and reveals nuances as the film progresses.

It's this vibrant life that Ashby and Gunn give the characters that raises The Landlord far beyond an intellectual racial satire and into a film with a heart that's just as big as its brain. Like his contemporary Robert Altman, Ashby is able to turn on a dime from expressionistic montages to intense, intimate moments. It can be as exhausting as it is awe-inspiring but it works wonders here. Ashby threads the needle throughout the film and somehow manages to tie together heartbreak, biting satire and huge laughs. For his first time in a director's chair, this balancing act is rather amazing.

After the tenants and his family are through their initial threats to kill or disown him, Elgar settles into his apartment and stumbles into a relationship with Lanie, a half African-half Irish dancer at a local nightclub. Their romance, like the film itself, starts out somewhat improbable before turning quite honest and touching. Marki Bey gives a strong performance as Lanie, the quintessential young, intelligent, independent, urban woman of the late 60s/early 70s. At first your not sure what Lanie sees in the naive Elgar, but as their relationship blossoms both Lanie and the audience fall for Elgar as we see him mature before our eyes.

But as naturally as boy meets girl, boy must of course lose girl before boy can really get girl. You see, one drunken night in Francine's apartment is all it took for Elgar to give himself over to her in a way that I think any hetero-minded male might jump at the chance to do. It's one of the best scenes in the film, spectacularly shot in long takes and lit by Willis in a dreamy red hue. And it's made even better by the lack of the regret-filled morning-after that usually follows these scenes. Instead, the morning after is just a continuation of Francine's tenderness and it's a refreshingly sweet moment. The regret comes a bit later, as Elgar and Lanie are settling in and Francine comes a-knocking with news that she's pregnant. This leads up to a hilarious visual joke as Elgar's mother's stands frozen and we cut away to her mind's eye as she pictures herself standing in the lawn singing to eight black children.

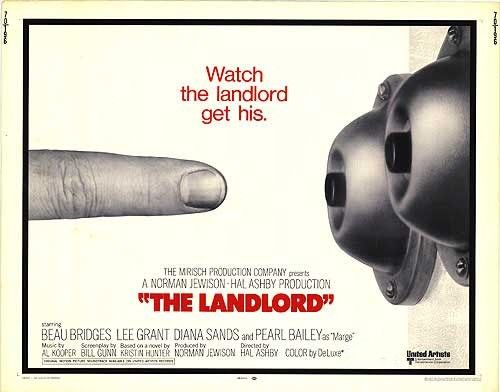

Even with an unexpected love-child being thrown into the picture, the film resists falling into any melodramatic traps or heading down any familiar, comfortable paths. The tone of the ending is a little typical of the rebellious movies of the time, such as the aforementioned Graduate, but it still defies predictability. The Landlord is constantly turning left when you think it's going to turn right and surprising you with its depth when you think it's going to be all style -- right up to the final scene. The movie is thoroughly unclassifiable and also nowhere near the film that the old cover for the VHS release was trying to sell.

There's enough bold experimentation (that works), hilariously memorable lines ("He just called us niggers," and just about everything else that comes out of the mouth of Lee Grant) and uniquely enjoyable characters to make the film a certified classic. And even though it is distinctly of its time (this is indeed your grandaddy's Park Slope) its message and themes are still meaningful and resonate stronger than most of the films that attempt to speak about race today.